LIFE: ★★★½

On Gene Beery

Art in America Magazine, November 2016

PDF | Web | GB

FOR MORE THAN fifty years, Gene Beery (b. 1937) has churned out words. Not words as they are typeset, but words as they are inscribed by a particular hand. Beery’s words, which appear in his countless paintings and books, often rendered in the unheroic style of sign painting, convey a specific voice that he has honed over the decades. This voice is peculiar, and not widely known; it speaks in slogans and jokes, spanning topics and tones. A representative sample of Beery’s paintings hanging together might read something like this:

THWART FATE / REVIRGINATE

BRAP! / SPUGG! / ZANKO! / IT AIN’T OVER TIL / THE DRUMMER / SOLOS!

ENOUGH!

STILL LIFE

PRACTICE QUOTIDIAN ECSTASY!

A NICE PAINTING TO BE READ ON A WALL IN ONE OF THOSE SECLUDED ROOMS WHERE SOME CONSPIRE TO TAKE ADVANTAGE OVER OTHERS

WE STILL HAVE WILD BIRDS HERE

I GAVE UP / IT'S WONDERFUL!

Though he had a brief, formative period in New York, Beery has spent most of his life working in the rural foothills of central California, in Sutter Creek, about an hour east of Sacramento. This has no doubt affected his visibility within the overwhelmingly cosmopolitan art world. But decades of steady transmissions from the foothills, including not only paintings and publications but also snapshot photography, video performances, and an idiosyncratic personal website, have all bolstered Beery’s cult status.

Among the founding members in Beery’s cult was his early friend, former neighbor, and lifelong supporter, Sol LeWitt. But in contrast to LeWitt’s tidy, stately rigor, Beery has embraced a rough, vernacular aesthetic. He lives like a backwoods Gauguin, but he also cultivates an existential cantankerousness that recalls Vonnegut. In his pastoral remove, Beery is a humorist whose bits aim both high and low, commingling crass puns and mortal dread. Using corny one-liners and low-budget materials, he tackles such heady, broad topics such as nature, semiotics, and art itself. But despite the bite of his self-effacing explorations of grand themes, Beery’s wordplay retains a bright-eyed optimism—even an affirmative humanism—in the face of a life and world where cynicism could be the more obvious response.

EUGENE B. BEERY was born in the industrial town of Racine, Wisconsin, to a working-class, staunchly Catholic, Germanic-Polish family. His father was a used car and vacuum cleaner salesman who painted watercolor landscapes in his spare time; his mother came from a family of mechanics and engineers. He briefly attended a local Catholic university and studied industrial design—a practical, money-conscious application of his creative impulses, suited to his upbringing—but decided to focus on fine art after taking a figure painting night class. While in school, he learned about contemporary art from magazines, including Art in America and ARTnews. The magazines made clear that New York “was where the action was,”1 and so in 1959 Beery quit college and drove to the city, seeking to unbridle his ambitions from his origins and enter the ranks of the American avant-garde.

The New York art world that Beery entered was smaller than todays and, in keeping with high modernism’s heroic tenor, more pugilistic. Beery set out to find where he stood, and how he could make his mark in an economy then characterized, according to Peter Schjeldahl, by “the terrible pressure for aesthetic novelty.”2 Abstract Expressionism was cresting, Pop was percolating, Rauschenberg was making combines. Like so many young artists, Beery observed these currents at openings and in bars. But he also gained additional insights while working as a security guard at the Museum of Modern Art (where he befriended LeWitt, a fellow guard). There, he watched over works by the modern masters (Cézanne, Matisse), noting not only their techniques but also their effects on the room. What got reactions from the crowds? What makes someone take pause in a cascade of masterpieces?

Beery noticed that one reliable way to make a MoMA visitor pause was text: ‘Art viewers were very interested in paintings with scraps of text, newspapers, notes like that,” he said in a recent interview with painter Joshua Abelow. “Words are a tool of the visual art experience; see Magritte, Stuart Davis.”3 But the “visual art experience” that interested Beery included words written by institutions as well as artists: explanatory wall texts, pamphlets, and signage more generally. Sometimes in the gallery you read more than you look.

Beery was especially inspired by one particular MoMA sign that he saw affixed to a kinetic sculpture by Jean Tinguely. In Beery’s telling, he encountered the sculpture on a day when it was malfunctioning. The museum had shut it off and hung an OUT OF ORDER sign on it. Beery was amused by the sign’s apparent incorporation into the assemblage artwork. The scene became the sort of dry, one-note jab at high sculture’s stuffy mores that makes for a quintessential New Yorker cartoon. What’s more, the sign’s sober, functional design stood out in what Beery has called the “spectral glut” of painterly pyrotechnics evident throughout the museum.4

The slippage of signs from commentary into content would prove the basis of Beery’s entire career; A gleeful prod, aimed at “proper taste,” would become his main mode of delivery. His first show in New York was a 1962 juried open-call exhibition at MoMA titled “Recent Painting U.S.A.: The Figure,” to which he submitted a salvaged Masonite slab, uniformly painted drab gray, with biomorphic add-ons and cut-outs labeled ARM, MRA, BREAST, and TSAERB (Strange Device Still Untested, 1960).

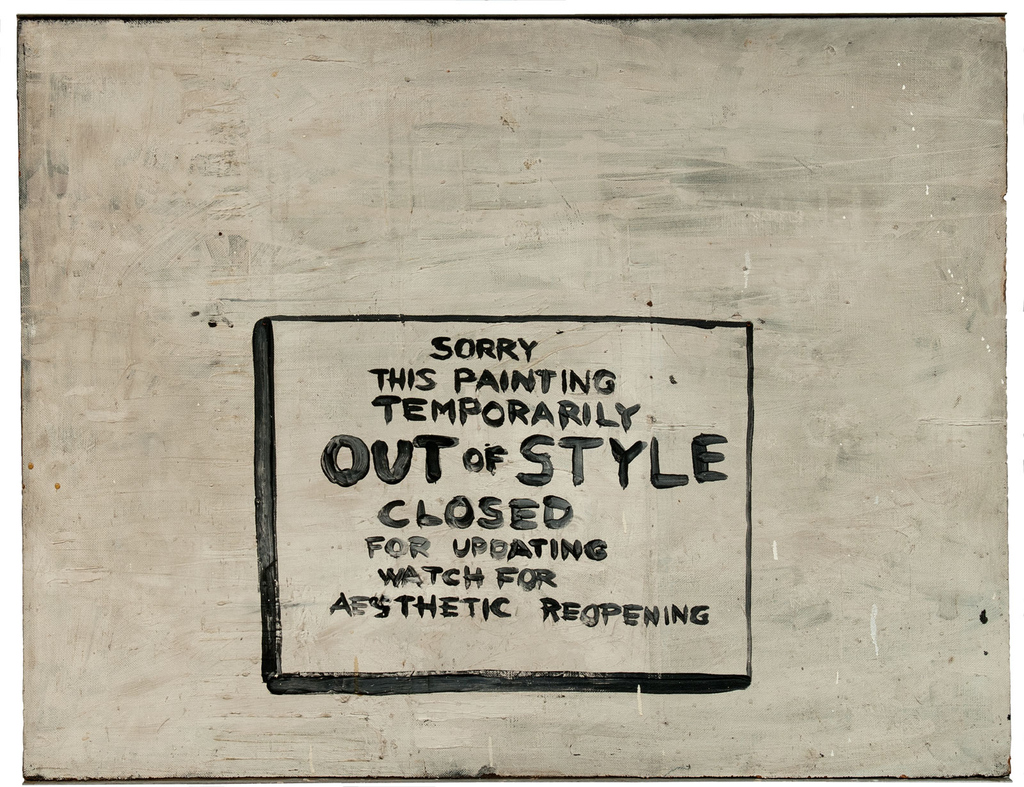

Within an otherwise conservative figure painting survey, Beery's quirky linguistic play and bizarre formed piqued the interest of at least one observer: Max Ernst. The German émigré eventually helped score Beery a slot at Alexander Iolas Gallery, which represented European Surrealist statesmen such as Ernst and Magritte, but had also held formative shows for younger artists such as Yves Klein, Ed Kienholz, and Andy Warhol. There, in 1963, Beery debuted his first all-text paintings, rendered in black on salvaged Masonite. One of these works, Out of Style (1961) reads:

SORRY / THIS PAINTING / TEMPORARILY / OUT OF STYLE / CLOSED / FOR UPDATING / WATCH FOR / AESTHETIC REOPENING.

This early work contains the kernel for most of what Beery has produced since. Its gruff capital letters, applied with demurely expressionistic brushwork, would become Beery’s go-to lettering style. Its blunt self-awareness also established a tone that Beery has maintained. The Iolas show featured several other jokes on canvas, similarly inscribed:

USE THIS / AS A PAINTING / IN AN / AESTHETIC / EMERGENCY / ONLY

THIS PAINTING MAY / ALSO BE UTILIZED AS A / PANEL IN A WALL FOR / BUILDING A PIGEON COOP / OR A ████

But as Out of Style shows, Beery’s humor is not simply a joke—it can also be scathing. It belies a young artist’s anxiety at the demand of genius in the presence of greats. In particular, Out of Style shows a morbid awareness of the brief shelf life of most artist’s careers, many artists’ lives, and the fickle ebbs and flows of attention which sustain them.

These concerns were (and are) commonly discussed in the social circles around art, but rarely had they been so explicitly made the subject of artworks. Ad Reinhardt had taken up this theme in his “How to Look” comics, but he famously divorced his satirical output from the “serious” work of his paintings. To do otherwise would be gauche—and gauche is exactly what Beery decided to be. Starting with his first gallery show, he made a habit of calling the bluffs of the reigning aesthetic elite—the language, themes, narratives, and behavior with which it ascribed and accrued value—while retaining an earnest faith in art-making itself. At Iolas there were no sales, no reviews.

It would take several years for the rest of the art world to tune in to the kind of text-based, reflexive critique that Beery was offering, and when it did, other players were at the forefront. Conceptual art, and its preoccupations with semiotics, formal austerity, seriality, and the critique of institutions, would gain traction only later on in the ’60s, albeit with a more academic inflection, and scrubbed clean of any trace of the artist’s hand.

BEERY’S DISCOMFORT with the New York art world’s politics, posturing, and raucous lifestyle proved untenable: in the same year as his solo debut, he quit the city, leaving his Hester Street loft full of works, a handful of which were salvaged by LeWitt, who lived upstairs at the time.5 He returned to Wisconsin for a spell, met and married his lifelong partner, Florence, and eventually moved to central California—first to Petaluma, where he commuted to San Francisco to drive cabs, and then to Sutter Creek, where he built a studio, raised a family, and continues to live to this day.

One might suspect that Beery would have found some kinship with West Coast Conceptualists like John Baldessari and Ed Ruscha, whose earliest experiments in text, humor, and meta-painting commenced some years after Beery produced his first major works. In fact, Beery’s paintings traveled with works by Baldessari and Ruscha, among others, as part of the series of “Numbers” shows that Lucy Lippard organized in the early 1970s. Yet having withdrawn from the New York art world, Beery made few attempts to ensconce himself in the burgeoning Los Angeles scene.

In Petaluma, far from the “spectral glut” of New York that he parried with austere gray panels, Beery developed a bolder, more expressive palette, leading to his most formally virtuosic works. His fixation on art about art loosened, and he began to incorporate themes from his new, more placid life—chiefly his proud role as a family man, and his proximity to nature. Just a Good Painting (1970) typifies these expansions. It includes multiple layers of text, each distinguished by a bold graphic treatment. The work’s title reads in huge, schmaltzy cursive, radiating hard-edge bands of color. A second phrase, THE HIGHEST ART / PARENTHO- / -OD ART!, appears in pink and blue capital letters, with even strokes of orange cutting off their peaks. A third, fainter text, rendered in orange, is tucked in the bleed between bigger words. It reads: ADDICTED / TO / NATURE. The whole composition is oddly cut off at the right, and the texts appear on top of a diuretic mustard monochrome that is suffused with dots of pigment. It’s enamoring in its expert queasiness.

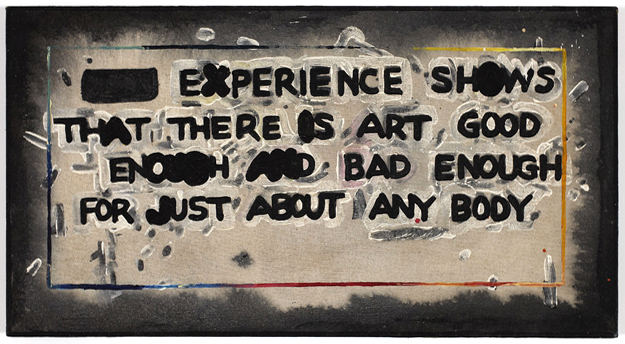

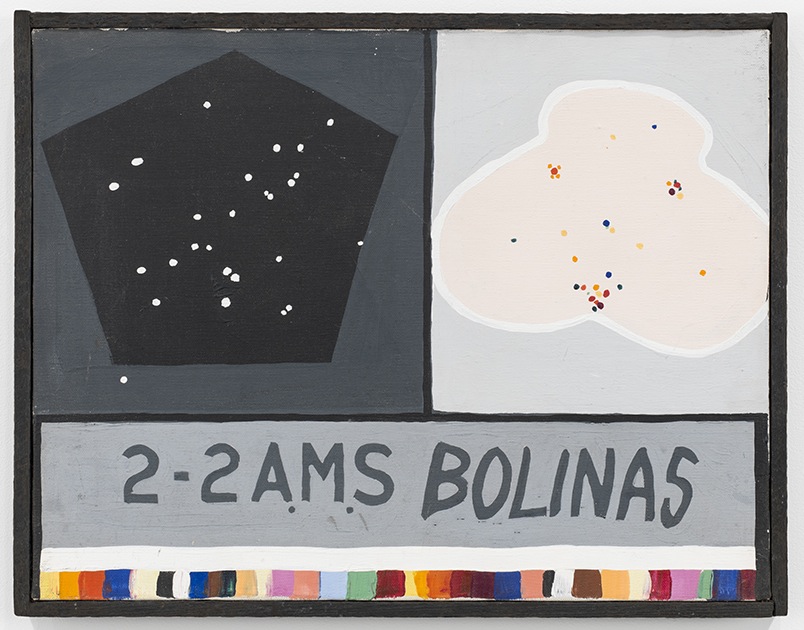

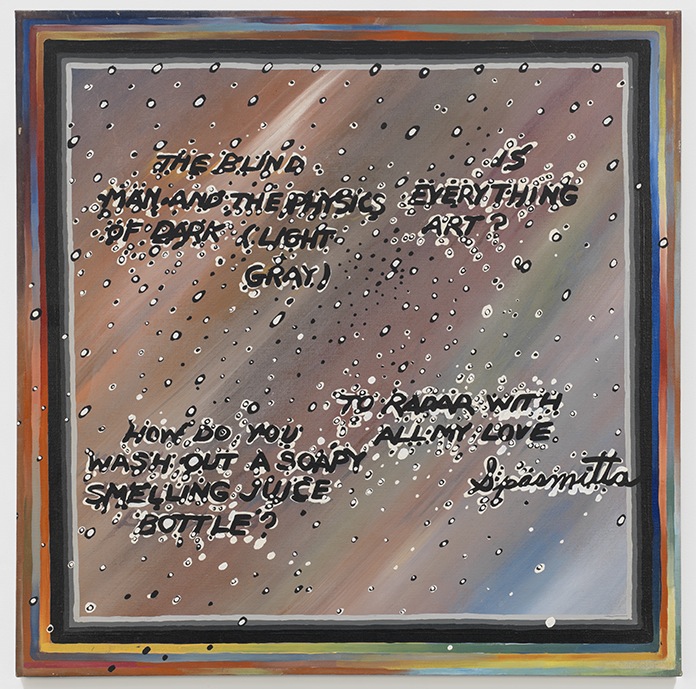

Beery’s work was wide-ranging during this period. He indulged in hallucinatory formal experiments, and he began to advance a beguiling, insular poetics—a phonetic dance of puns, whimsical phrases, and neologisms. In Experience Shows (1970), he toys with letterforms and paints the same letters repeatedly until they fall off the edge of discernibility. Fragments of landscapes appear in some works. Constellations painted from star charts are just visible in others. In The Ethical Crisis Playoffs (ca. 1970s), he concocts a tournament bracket of artist tropes, including COCKY YOUTHFUL SNIPPETS; REVOLUTIONARY, EVILUTIONARY, INVOLUTIONARIANS; and ELECTRONIC MEDIA-OCHRE SERENITY CONFABULATORS. The final round comes down to JOLLY WED COPULATORS versus KICKY HEROINITE NODDYS, but the champ remains undetermined, a blank space circled by cartoonish exclamatory lines:

Similarly inventive sequences can be found in Beery’s many books. (LeWitt provided the funding for dozens of these publications in the ’70s and ’80s.) Beery tends to treat each page like a text painting made with Sharpie. Many of the spreads in Art Test (1987) are devoted to a search for a “universal art symbol” on the level of ♥ for love, or ☮ for peace. Page after page is filled with inscrutable squiggles and commentary on various approaches to iconicity (A FINITE IRREPRESSIBLE SPECIFIC AESTHETIC VISUALIZATION OF A BINOCULATE PRETZEL AS A HEURISTIC SUGGESTION IN QUEST OF THE UNIVERSAL ART SYMBOL). The books allow Beery to twirl an idea repeatedly, free from the traditional monadism of painting. Manifesto! (1978) pairs seemingly earnest declarations of art’s function and merit with increasingly cheesy puns on “manifesto” (MANY FATSOS; MIGHT SPENT JOKE).

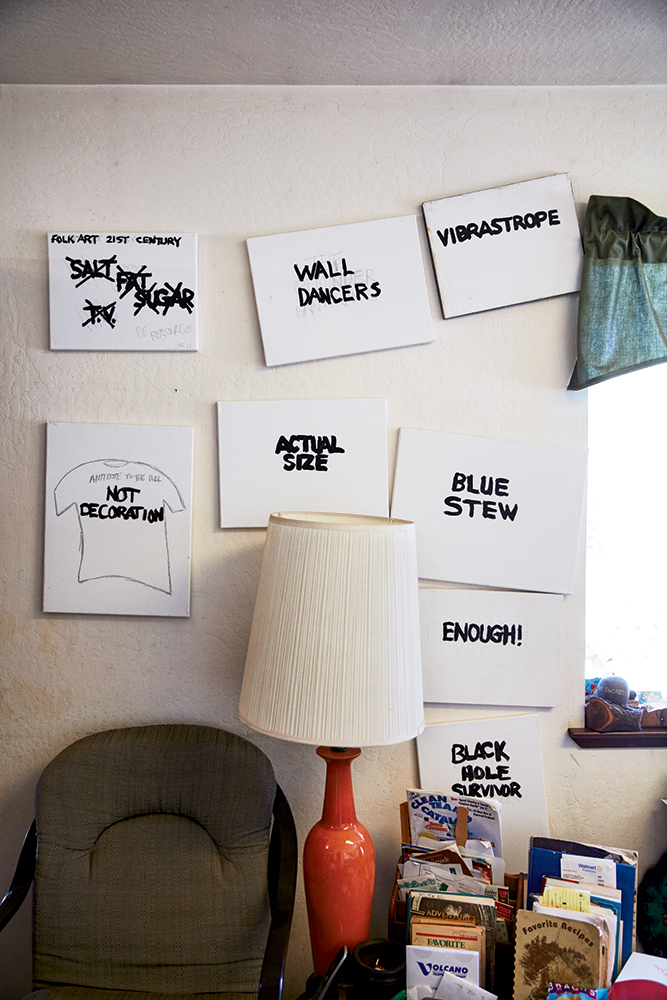

Along the way, Beery’s paintings came to look more like the pages of his books: black on white, quickly executed. By the 1990s, his exuberance transferred from focused, intensive technical labor to rapid-fire production, in the service of ideas. As he told Abelow, “the ideas were coming so fast I wanted to get them down before they slipped away or I got a better idea.”6 More and more, he pared down the expression of these ideas to black acrylic on startchy, pre-stretched canvases from Walmart (there are no art supply stores in Sutter Creek, and not much more money). This is mostly how he works today. Each whim gets a canvas, usually small. Sometimes they are as succinct as STILL LIFE, A POEM, or VIBRASTROPE; others continue his penchant for enumerative lists, like STILL CHAMPIONS!!! (1994), which pits cars against various types of roadkill (AUTO DRIVERS 8; SKUNKS 0). He treats his paintings unpreciously, sometimes repeating phrases from earlier works. Ambiguously dated canvases pile up in his home. When the weather is good, he paints outside and hangs finished pieces on the exterior of his house:

IN A WAY, Beery’s unfussy mode of making retains Conceptualism’s early dream of dematerialization, and the commodity critique that partly fueled it. Whereas more canonized Conceptual practices eventually calcified into the very type of rarefied, marketable art objects that they had set out to dismantle, Beery retains the attitude that it’s the idea that is precious, not the thing itself. Of course, it’s somewhat ironic that he expresses this attitude through painting—arguably the most salable medium and a frequent target of Conceptualist attacks. But his recent fast-and-loose production upsets painting’s presumed sanctity and value.

The recent works make the most sense when viewed serially, where the flow of whims can accumulate into something more powerful than any one thought or canvas. In constellation they suggest an equality of ideas, taking the big with the small, the smart with the dumb, complementing Lippard’s claim in Six Years that “judgment of ideas is less interesting than following ideas through.” Beery often calls himself a “visual percussionist,” suggesting that the rhythm and sequence of simple elements are what produce interest. Still, he delights in specific moments of painterly gesture, compounding the transcendence of idea art with the immanence of looking: he will work his letters over, smudging, redrafting, and redacting lines, betraying precision and intention beneath his apparent slop. Such moments help his work emit a humanity that is alien to both Joseph Kosuth’s cold analysis and Baldessari’s ironizing distance. Beery’s works remain flawed, vulnerable, warm.

At the time of this writing, Beery’s place in the canon remains somewhat tenuous, but things are looking up. He has yet to have a museum show, but a younger generation of artists, curators, and gallerists continue to join his cult. Abelow is perhaps Beery’s most vocal advocate, having evangelized about Beery at length on ART BLOG ART BLOG and presented his work at Baltimore’s Freddy gallery. Lower East Side galleries like Bodega, Simone Subal, and Lisa Cooley have all paid homage to Beery, by including his canvases in group exhibitions. There’s a strange prescience in Beery’s succinct, easily disseminable, junk-heap poetics that seems ready for the Web. Beery’s text paintings also hang weirdly well, it turns out, alongside works by younger artists such as Nicholas Buffon, Lily van der Stokker, Mathew Cerletty, and Abelow. He’s a loopy grandpa we never knew we had.

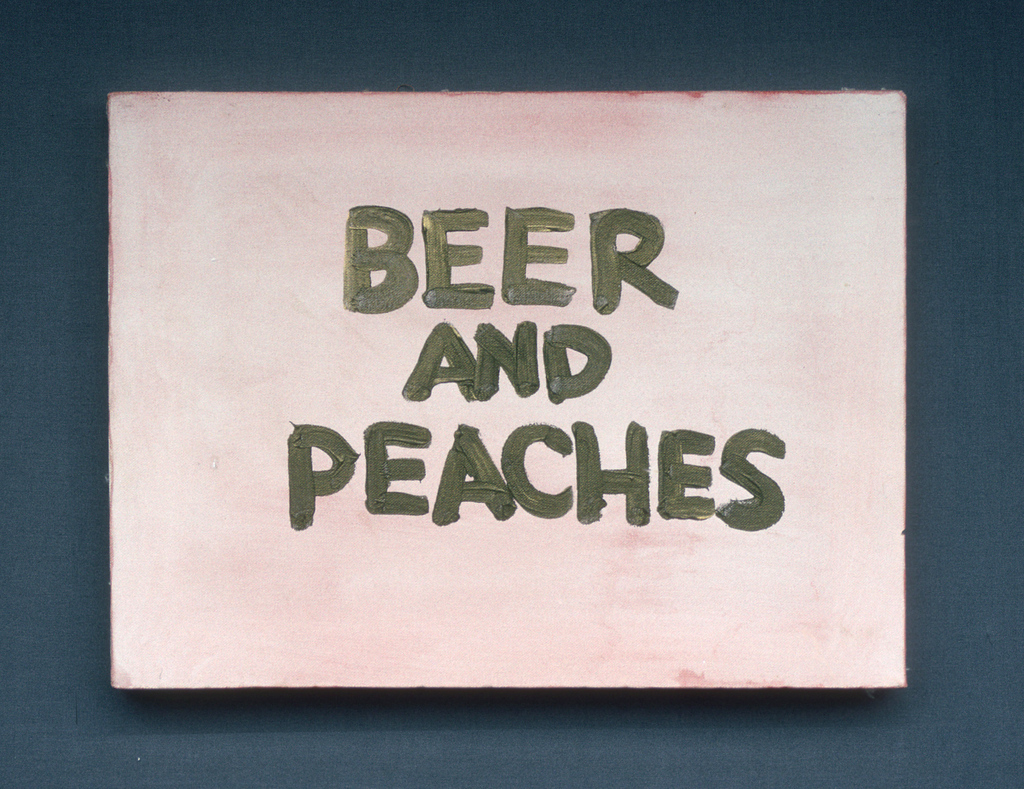

But for Beery today, success is not measured by visibility or influence. His life isn't about wine and cheese, but “Beer and Peaches”, as the title of one 1991 painting goes. This became clear to me when I made the drive to visit him in Sutter Creek this past August. Looking around while Gene fixed us sandwiches, I realized that, in a sense, his works are not made for the white cube—they are made for the ranch, for his grandkids, for Flo, who passed away last year. Above his sink hung a quadriptych charting the first names of Beery family members—but even here, Gene’s penchant for pedantics showed in the “key”:

THE BEERY FAMILY’S / FIRST NAME PORTRAITS. / IDEAL PROPORTION / AXIOM. / RELEVANT MYTH.

To the left, above the fridge, was a “formal portrait” listing their post-office-box address. It became clearer why Gene’s snapshot photography has been so central to his website, and to recent exhibitions—paintings resting on the sofa, he and his family playing games in homemade masks, paintings wrapped on the wall on Christmas Day. The work thrives on-site, “art into life.”

Later, we drank beery in folding chairs under a tarp in the yard, looking at an arrangement of “T-shirt paintings” (showing shirts adorned with slogans) that Gene had composed on the side of his home. We talked about his professional regrets, and his “what-ifs,” but mostly about his pride in his life and career built otherwise. A 2014 painting offers a retrospective assessment:

LIFE: ★★★½

He told me, “in the city you don’t get a full slice of life. You don”t get a true sense of death, either—out here, you learn to live with death, and you learn to live with beauty too.” Crickets chirped; a deer walked by; one T-shirt read, its right arm extended:

I DON’T WANT TO THINK OF ANY LAST BREATHS!

***

- Gregor Quack, “Interview with Gene Beery,” July 2016, jan-kaps.com.

- Peter Schjeldahl, “Hartford: Echoes of the ’60s,” New York Times, January 27, 1980.

- Joshua Abelow, “Interview with Gene Beery,” ART BLOG ART BLOG, March 2013, artblogartblog.com.

- Beery in conversation with the author, Sutter Creek, Calif., Aug. 15, 2016.

- LeWitt’s support over the years would sustain Beery’s practice and help keep him tethered, somewhat, to the Conceptual legacy. In addition to funding the production of Beery’s many artist books, Lewitt had a hand in Beery’s inclusion in Lucy Lippard’s 1973 compendium, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object, as well as two of her “Numbers” shows. For a time, Out of Style hung in his studio. Moreover, LeWitt’s loan of the salvaged loft works to the Wadsworth Atheneum for a MATRIX show in 1979 was key to Beery’s rediscovery: it was there that gallerist Mitchell Algus first learned about Beery, and he would go on to represent and exhibit Beery through the ’90s and early 2000s.

- Abelow, “Interview with Gene Beery.”

Thanks to:

Gene Beery, William S. Smith, Leigh Anne Miller, Eric Veit & Elyse Derosia, Joshua Abelow, Jason Frank Rothenberg, Sam Korman, Robert Snowden, Jordan Stein, Mitchell Algus, Amy Greenspon, Chris Viaggio, Jan Kaps, Teresa & Pamela, Matthew Shen Goodman, Amy Egerton Wiley, Tony Chrenka, Cora Walters, and Rebecca Peel.