The Angriest Dog in the World: an essay performed to an audience of familiars in Portland, Oregon, on March 3, 2016.

Publication

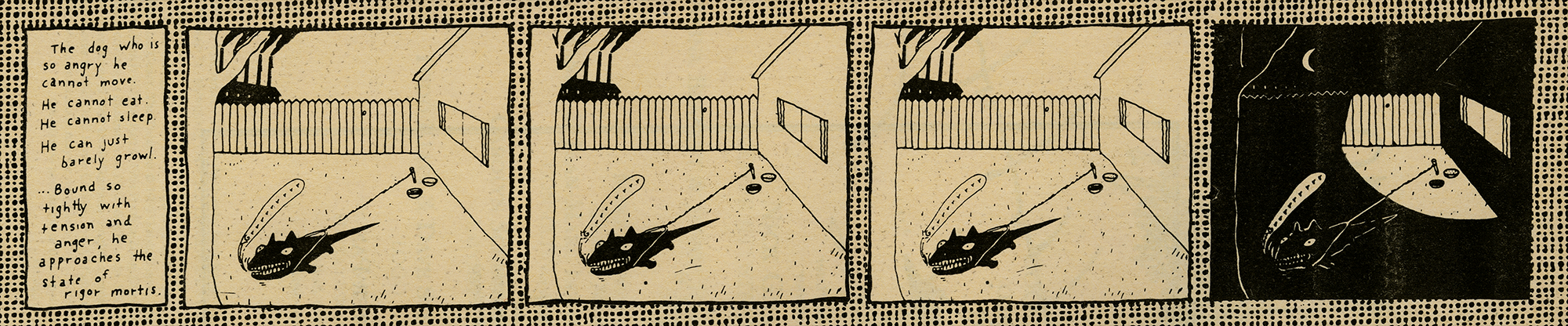

“The dog who is

so angry he

cannot move.

He cannot eat.

He cannot sleep.

He can just

barely growl.

…Bound so

tightly with

tension and

anger, he

approaches the

state of

rigor mortis.”

This is the song of The Angriest Dog in the World. He is a character by David Lynch, whom we know best as a filmmaker, though for the past decade he has mostly worked as the face of the Transcendental Meditation® technique for inner peace and wellness. He has a coffee bean brand, an internationally touring painting retrospective, and two mostly unfortunate pop records. He is maybe a bit obnoxious these days. But you could say he is on a victory lap—which makes sense when you’re 70 years old and one of the most distinct voices in popular American cinema. Bonus points for being a bit of a populist’s avant-gardist, exposing a relatively broad audience to relatively far-out ideas—including me and many other suburban teens with a taste for “dark shit.” I ended up writing my high school thesis on his painterly treatment of cinematic composition.

Though we are told his concept is as old as that of Eraserhead—that’s 1973—The Angriest Dog in the World appeared weekly from 1983 to 1992 in the back of The LA Reader, an alternative news rag similar to the Portland Mercury. The LA Reader’s other Googleable achievement appears to be that it published the first strips of Matt Groening’s Life In Hell. But while Groening’s strips were a main attraction, sprawling across full pages, Lynch’s identical panels and useless dialogue were holed up in the back, fit between restaurant listings and billiards ads. A rock in the sock of ad revenue. His dual charms of taking up space and providing name recognition took him to other small papers, including Atlanta’s Creative Loafing, Denver’s Westword, and New York Press. When the Reader folded in 1992, the Dog went with it. From 1991 to 1993 Dark Horse Comics republished two strips per issue of their anthology Cheval Noir—that’s 19 issues, so 38 strips out of approximately 500 iterations of the same drawing with different word bubbles pasted onto it over a decade. Outside of bad scans online, these 38 are the only readily obtainable prints of the strip. They are the ones running on these slides, and populating the booklet by the door. From what I can tell, they are no less unremarkable than the other 400-something.

I like the comics. They are shitty. Shitty, dumb, and blunt—especially so for an artist known for meticulousness, density, and ambiguity. Their shittiness makes it hard to justify “analyzing” the strip. A critic might strain to make something of the comic’s treatment of text, but its dumbness defuses that. I would prefer not to try. The strip hits hardest, I think, in the long view: when it is seen as a continuous project altered weekly. Each Monday, an envelope to a publisher. Each Friday, a murmur in the restaurant listings. A decade of inertness accrued, one frame after another. America’s favorite surrealist was playing a conceptualist’s game.

David Lynch has never had too much to say about his Dog. When asked, he has kept it brief and simple. Why did he make the comic? Because he was angry. Correction: he *had been* angry. In one interview, he insists: “the memory of anger is what does ‘The Angriest Dog.’ Not the actual anger anymore.” Elsewhere: “I had tremendous anger. When I began meditating, one of the first things that left was a great chunk of that. I don’t know how, it just evaporated.” How nice for David Lynch.

It is not my experience that anger evaporates. Nor that anger and the memory of anger are separable pools. For a filmmaker known for finding hell in heaven, and heaven in hell, Lynch’s refusal of negative feeling, here and elsewhere in his Transcendental evangelism, confounds me. I do not believe him. I do not trust the banishment of negative feeling. The American tale of redemption, salvation, the Bootstraps struggle. The drive toward a smooth and structured mind—we hear this from all sides, all the time. How nice for those who find themselves within it.

But at the same time there is still the ineffable fact of the Dog. The Dog without a Heaven, approaching the state of rigor mortis, weekly—perpetually—recorded for 500 days and nights. His state is as insistent as the vice grip on the American underclass.

As stagnant as wages.As cruel as fast food.

As tacit yet flagrant as state violence.

As steady as the block of reruns that my mother binges on nightly; her eyes, like his, wide throughout the night, presented with insurance policies and evangelists, and the sound of other people’s laughter. Boxed wine churning, corroding her stomach. Each too broken to leave their post, my mom and the dog are still stuck breathing for a while yet.

The strip in all its dumb, mute brutality is Lynch’s moment of realism, his crudest marriage of banality and Hell. The Angriest Dog in the World is his most American story. Yet he would have us believe that he himself is beyond its subject.

…

I don’t know what more Lynch can do for us here. Actually, when I think about the Dog, I like to set Lynch aside, as best I can. He is an author who overwhelms his output. Typically, the Dog lives in his creator’s shadow, a curious ornament of Lynch’s eccentric eclecticism, known mostly by diehards. There, he is merely a “deep cut.” When I remember that in Cheval Noir Lynch’s name appears more crisply than the dog’s, I flinch. This feels unfair. I am less interested in how the Dog serves Lynch and his authority than how the Dog serves himself, and how he can serve us, maybe against his master’s intentions. I think of him as a mascot for negative affect—the feelings which Lynch himself disavows—whose expression of anger rings more true to me than most media depictions. The dog pricks me. I lie beside him. We stare, and growl, and approach the state of rigor mortis. We seethe.

Seething is a sullen type of anger. In opposition to anger as a flame, as violence, yelling, broken plates or mirrors. Contagious, spectacular anger. The Dog, instead, is a smoldering log. Maybe it’s surprising that The Angriest Dog in the World has no bark and no bite. But seething is concerned less with fanning out into the world than with keeping a lid on it. (Or keeping a screen in front of it.) I used to think of anger as an event, a rupture, an thus a moment of opportunity. But now I know anger as the baseline between outbursts. Seething is not a switch but a sieve. It is the pain, quotidian. It is an imperceptible atrophy. This can be consuming.

Day in and day out the dog lies prone, exposed to the elements, exposed to the noise of his owners. His bowls never empty. He is not dead, but he’s not exactly living a life, either. No eating, no sleeping, and no actions that these basic needs tend to afford. He lives in negation. He lives *as* negation—but with none of the liberty or joy of refusal. We cannot commend him for anything; he is no radical. This is not a decision. It is a sorry state.

While he “cannot move,” he is not without motion: to quote his refrain, he “*approaches* the state of rigor mortis.” What propels this approach, this death drive? His little growl. This frail, measly word bubble, humming like a motor, is the dog’s constant companion. Its letters are barely letters, so crassly inscribed, each R a shrug of the pen. But at least it’s reliable. It is a limb. It is a nightlight. Like steam from a kettle, the bubble’s steady emission betrays an inner chaos; the otherwise untraceable pain that is steeping within our dog. My suspicion is that his exhaustion does not come from emptiness, but from fullness: that so much is inside that nothing really gets out, spare his monotonous rumble of sound. The dog is fatally congested.

He’s opaque, sure, but sometimes that’s right. It is not that he is simply dumb: he is dumb*struck.* Struck dumb so deep that the source can’t be spoken. I think of Santi—maybe you know him—staring, as he does, through everything and past everything. I think of every public school teacher that I have ever known. I think of Andrea, publicly misgendered by their curator, their supposed advocate, and how this must be the thousandth time, humiliating and not quite surprising. I think of my father, staring at his zero-dollar paycheck, standing on the asphalt of the used car lot he calls home, his knees swelling, our house foreclosed, his disease growing. I think of Frankie, his father in prison and then dead.

…

Words are stupid. This is a fact that the strip beats us over the head with. Whether pun or platitude, the words of Bill, Pete, Sylvia, and Pete Jr. universally ring hollow. To point this out is, in itself, uninteresting. Middle school stuff. But the real joke is that the strip treats the very *act* of speaking, or any kind of assertion into a shared world, *as* a joke. That all speech is a non sequitur to pain. That in his complete myopia, his dissolution into the dirt, the dog is somehow taking a more sensible path. Why this is funny, and why this is terrifying, I couldn’t possibly convey to you. To explain a joke is to kill it. But if you know depression, you may know how this one goes.

Only once has the strip’s dialogue actually meant anything to me. Cheval Noir, Issue 26, first strip, third panel: “People are dying living here.”

People are dying living here.People are dying living here.

People are dying living here.

When I organized an exhibition about seething last year, here in Portland, I cut this strip out and nailed it up outside the show. I didn’t really talk about it, but secretly, and not without shame, I wanted to mobilize it. I wanted it to be the moment where you kill a joke by saying “No, but seriously.” I wanted it to cut through the general inanity of the comic, the inanity of group shows, the inanity of art, of our enterprise, our faith, our delusions. Why we circulate at all. Why we should even exist. I wanted it to be about Portland: its white, well-fed face and the black, brown and poor bodies it’s tacitly steamrolling this very second to make space for even wealthier, white, well-fed faces. The way New Seasons perpetuates old cycles. The way our lifestyle entails death. I wanted you to feel bad.