Petrichor

Broadsheet essay for Erin Jane Nelson's exhibition, Petrichor

Document, Chicago, March 2015

PDF | EJN | Document

A paradox: while high culture remains, by definition, socially exclusionary, the pluralism of its references continues to grow. Think of Richard Prince, or the films of Harmony Korine, or A.P.C. x Carhartt. It’s not news that high culture refreshes itself by reaching down. Low stuff has found itself in lofty contexts for a long time, ushered in by provocateurs with mixed motives of populism (commendable) and cultural fetishization (not so much). In contemporary art in particular, those interests have coincided so often that they’ve come to appear inseparable — a queasy horizon. But since it’s there, we’d do well to retain a healthy skepticism: who benefits from such an interjection, and to whom or what does the artist appeal by sparking it? How might an artist speak from below, when historically their job entails speaking above the din? And how might they position themselves in relation to their references?

Signs get torn from their contexts. That’s also not news. But as with so many things, the internet has has served as an amplifier of this state — its promise so often figured as infinite access to everything, from everywhere, with a structure whose horizontality is so often mistaken for democracy. For many artists who grew up with that promise in place, the creative imperative is less to ‘construct’ meaning and more to sift it from the informatic deluge. They are diviners of “image ecologies,” tracking the flows of signs between contexts and consumers. They cite, they make playlists, they cut and paste. They agglomerate materials and images that enact or envision the dissonance of networked life.

It’s a gold rush, then, and unmined imageries are at a premium. In this expanded field of imageries, so much distinction hinges on the territories you choose to squat. My concern is not whether such mining should occur; it has, and it will. Instead, I’d like to put more focus on the motives subtending the extraction of images. In a word, I’d like to think about conscience, with an emphasis on social value and, untrendingly, class.

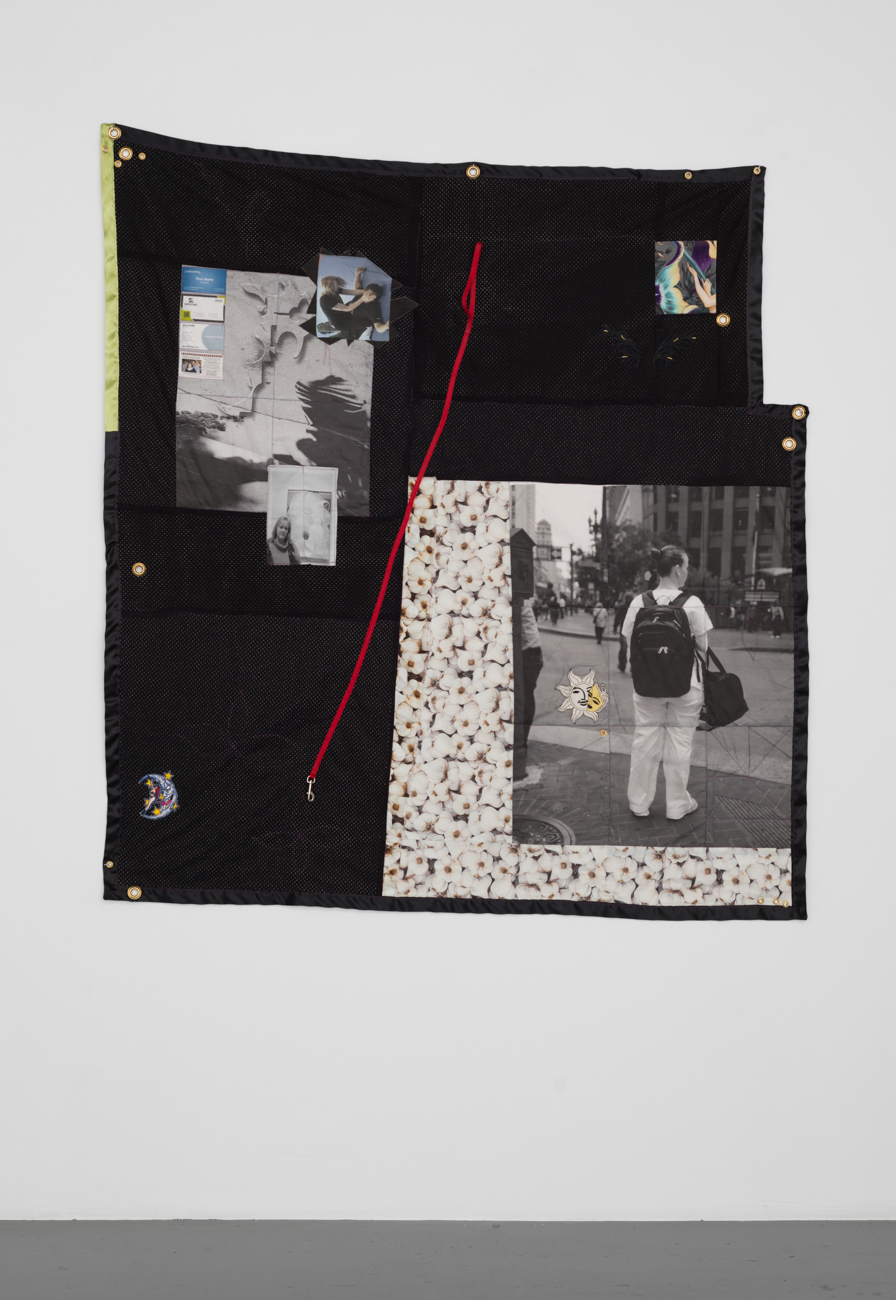

But actually dealing with the social is messy. It prompts thinking on tensions, and in an era that prefers to think of itself in terms of infinite, frictionless exchangeability, that’s a buzzkill. Lots of people prefer to play it safe, but Erin Jane Nelson dives in with candor. Her photographs depict street scenes from the San Francisco bay area, itself a sociological knot of poverty, tech money, radicalism, and an array of wilting utopian ideals. As befits the tradition of street photography which she extends (itself non-“Fine”), she doesn’t unravel that knot — she prods it. A mess of signs for messy times: Erin embeds her photographs in heaps of vernacular, pulling in bawdy iron-on patches, rock tumblers, bird cages, wine stains, cigarette burns, and the Dead Kennedys logo, to start.

A minefield, maybe. In the hands of some artists, such extensive representation of underclass stuff might read as icky. Why’s it there? Because it *can* be, because it’s ‘other,’ because I say so. For Erin, the “why” contains more weight. This has to do in part with her own uneasy relation to the class presumptions of artists and their origins. A glut of ambivalence, then: there’s compassion, there’s doubt, and though there’s humor, it’s not fully steeped in irony. Above all there’s a cautious compassion for the dissensus of populism, and that’s what Erin tracks from the middle. Her quilts, prints, and sculptures suggest an interest in testing boundaries of legibility, and an ethic of embedded observation that is both reportorial and poetic without fussing over their own worth.

Erin performs self-conscious assessments of distance: between self and other; sympathy and empathy; image as object and image as objectifier. Such distances are not fixed but teeming, especially in the lives of cities. The photos in this show come from Erin’s commutes between Oakland, where she lives, and San Francisco, where she earns her living. In the passage between, she shoots strangers. And while there’s often warmth toward these fellow travelers, the images don’t gloss over their sinister implications. After all, cameras capture: they constrain. But even with that violence in view, Erin holds out for sympathy, commiseration. Sentimentality has limits, no doubt, but at least it gestures toward an ethics. And maybe that’s what we need. The dispersion of images is not a smorgasbord of free-floating signs in a browser. It involves not just eyes and screens but bodies, communities, power — entire social and ecological matrices in flux. It’s precarious stuff, and Erin doesn’t try to exempt herself: just as a camera cannot know its subject, it also can’t make its user a disembodied eye, anonymous and neutral. Erin knows that subsumption has stakes for both sides.

And subsumption into what? In this show, images get channeled into dense compounds that delight in their materiality (though not ceremoniously: Erin insistently staves off preciousness with stains, burns, holes, puns, frays). In some cases, they’ve culminated in quilts. The medium of the quilt — itself a vernacular citation — connotes craft, care, and the wish to warm. In addition to its empathetic implications, Erin is interested in quilting’s direct correlation of effort and value. It’s with that correlation in mind that she goes maximal, with elaborate stitching, siding, flocking, flourish, probing value through flurries of laborious gesture.

But let’s also not forget that quilts are traditional vessels for community and memory — think of the women of Gee’s Bend, or Cleve Jones’s AIDS Memorial Quilt. In cases like these, quilts are not simply objects which circulate among individuals. They also model relational structures outright, enjoining aesthetic form to social formation. Such convergences — or at least the fantasy of their realization — might point to the horizon of Erin’s image conscience. They contain an optimistic gambit that in art, social concern need not be presented coldly, that pleasure and politics need each other, as a quilt needs its backing.